I’m Tom Averill, author of the culinary novel Secrets of the Tsil Café, and a “foodie” in my kitchen and in my library.

When I was writing my book, I became aware of how important food is to our identities as people, and how food memories shape us. Cookbook writer Molly Katzen first learned the power of food at her childhood dinner table. Her father had served in World War II, and while he was overseas, his mother died. His favorite of all her dishes was tzimmes, a casserole dish of potatoes and onion and carrots often served at Rosh Hashanah. Each year, Molly’s mother tried to replicate her mother-in-law’s recipe, and each year she failed—until the time her father tasted the tzimmes and broke down sobbing; his mother had come back to life in that dish. Molly was 10 years old. Perhaps all of us miss a person, along with the dish that person traditionally brought to the holiday meal.

I grew up in a gustatory home. My mother was from the East Coast, my father from the West. Mother loved scrapple and Lebanon bologna, lobster and crab. My father loved artichokes and capers, garlic and onion. By the time I was 10, I had preferences. Visiting family friends one Christmas, I sat down to a delicious casserole. I picked the onions, sweet and slightly burned, from the dish and set them to the side. The nice grandmother of the family commiserated: “I didn’t like onions when I was your age, either.”

“I love onions,” I told her. “So much I’m saving them for dessert!”

On a family vacation, when I was 12 years old, we stopped in Washington, D.C., where my mother had a very rich uncle. He loaned us his chauffeur for all the sites, then met us for dinner at the very elegant Terrace Restaurant in the Shoreham Hotel. All vacation, my brothers and sister had ordered the same meal: hamburgers, French fries, and Coke. They did again, but I studied the menu, and found what I thought the most exotic item: Trout Almondine. My great uncle raised his eyebrows at that. I knew I’d impressed him, and when the meal arrived, he asked what I thought. “Delicious,” I said, and he raised his eyes again. “I never trusted it,” he said. “They fly the fish from the Rocky Mountains.” So I had not impressed him—only myself!

I also prided myself on my willingness to eat anything and everything. One day I taught myself to cook beef tongue. My sister called and asked if two boys could come to dinner, and I said, “Sure, if they’ll eat tongue.” After some hesitation, they did, and they liked it. Next day, they bragged about their culinary daring on the grade school playground, even came to fists with unbelieving classmates. They were sent to the office, but each year they returned to our house for what we called their “Weird Food Pig Out”—brains and eggs, kidney pie, beef heart, lamb fries and so on.

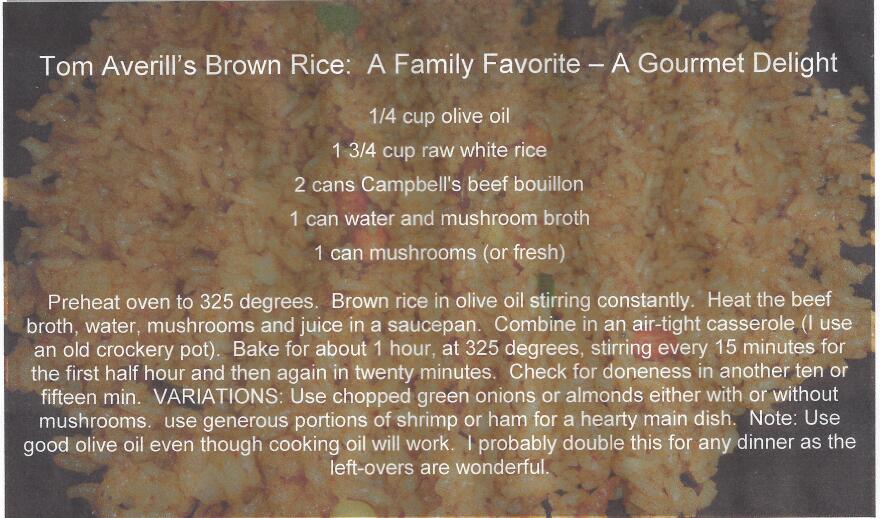

Food was so important to our family, that as my mother was in hospice care, slowly dying, she requested what she called “last suppers.” Lobster, artichokes, her brown rice, steak tartare, a good pesto from my garden, bagel and lox with plenty of red onion and capers. Tiny portions for the last portion of her life. She had many signature dishes, because we place our signatures on food, too. We are, after all, what we eat, defined by what we will or will not eat, and by how we remember food and family identity.

This is Food Friday and you’ll find recipes and stories by clicking Radio Readers Book Club under the Features menu at HPPR.org.