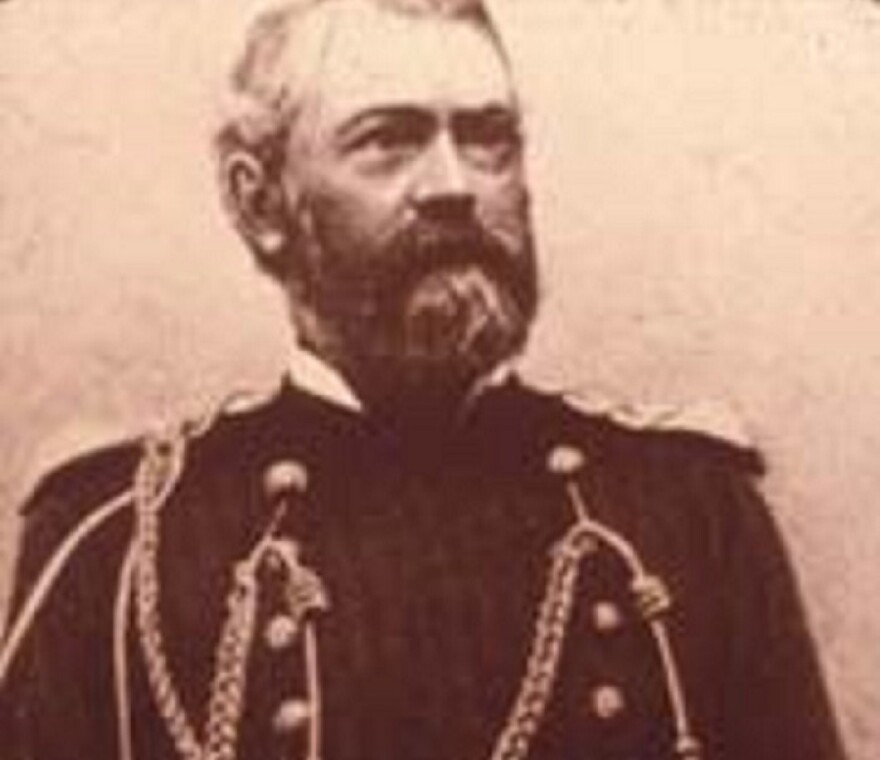

The early frontiersman Ricard I. Dodge wrote that “the first experience of the plains, like the first sail … is apt to be sickening. This once overcome” Dodge continued, “the nerves stiffen, the senses expand, and man begins to realise the magnificence of being.”

Since I grew up on the Plains, they never intimidated me the way Dodge said they do new arrivals. But that phrase “magnificence of being” perfectly describes how I still feel whenever I step onto open grasslands.

The Plains must have been even more glorious and magnificent in Dodge’s time, when buffalo were so numerous they “blackened” the land. On an 1868 western Kansas train trip, he reported crossing “through an almost unbroken herd” 120 miles long.

By 1873, he mourned the loss of those herds. He wrote, “Where there were myriads of buffalo a year before, there were now myriads of carcasses. The air was foul with a sickening stench, and the vast plain, which only a short twelvemonth before teemed with animal life, was a dead, solitary, putrid desert.”

Dodge was himself an avid hunter. “To the sportsman,” he wrote, “the most prominent fascination of the plains is the abundance and variety of game.” He had “[t]he most delightful hunting” of his life, he added, on an expedition along a tributary of the Cimarron River. He boasted a “total head bagged” on that hunt of 1262 animals.

These included 127 buffalo. Dodge took care to explain that these had been taken by the three Englishmen who accompanied him. He didn’t consider it sporting to kill an animal who would just stand still as bullets dropped herd mates either side of it. He had nothing but contempt for “hidemen,” the hunters who poured over the land, taking only hides and leaving carcasses to rot.

But he listed with seeming pride everything else that he and his mates killed on that expedition: 11 antelope, 20 deer, 793 game birds including turkeys, quail, grouse, and six species of duck, and virtually every other thing that crawled, walked or flew: badgers, raccoons, herons, plovers, hawks, owls, meadowlarks. Dodge doesn’t say whether the game animals were somehow stored for consumption, but the remainder could not have gone to any use, with the exception of a bluebird, whose feathers, he wrote, were destined to adorn a lady’s hat.

Dodge was evolved in consciousness beyond your average Joe. He noticed what his senses perceived and noticed the effect of those perceptions on his inner being. But that magnificence he so beautifully extolled must have given him a false sense of plenitude. Else how could he have killed so many animals so heedlessly?

I do get this somewhat. Life on the plains must have appeared limitless in Dodge’s time. He didn’t seem to realize he was taking part in the destruction of the place that gave him his greatest joy. Few understood back then how interwoven life is. Each meadowlark song and glide of the hawk contributes to the magnificence and to the seamless whole.

Entertaining a false sense of plenitude today would require us to shut down our senses and willfully close our minds. As went the buffalo and the tribes that depended on them for sustenance, so have gone almost all the original grasslands and the animals who thrived there. So have gone much of the topsoil and much of the underlying water.

The world is not as large and impervious to us as we once thought. We can harm it, and we are harming it. That is why we must make every effort to protect the magnificence that remains.