You wouldn’t know from just a glance around downtown Marysville that Marshall County residents are getting their COVID-19 vaccination at a higher rate than nearly every other place across Kansas.

There are rarely visible lines for doses.

Sure, the county health department pulled off successful mass vaccination clinics in Marysville’s historic train depot early on in the vaccine rollout. But most days, the department sees just a trickle of people coming in. Even those numbers have been dropping a bit.

Nor do county residents seem especially wary of the pandemic. Outside of the county health department, face masks were a rare site in many public areas in early summer.

Yet Marshall County has emerged as one of the state’s biggest success stories in terms of getting a large percentage of county residents vaccinated against COVID-19. More than half of the county’s 9,800 people have received at least one dose of a vaccine, according to the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. That’s more than 6 percentage points higher than the state’s overall rate of about 44%.

About 48% of residents have completed a vaccination series, well above the state average of 39% and more than any other county in Kansas as of July 6.

Marshall County’s experience challenges a narrative that conservative areas of the U.S. are more reluctant to get the vaccine than those living in urban and suburban areas. It joins a handful of other red, rural Kansas counties – about 73% of Marshall County voters cast ballots to reelect President Donald Trump in 2020 — that are also achieving high vaccination rates.

The county’s success isn’t being driven by anything particularly attention-grabbing, such as the vaccine lotteries that other states have been using to promote uptake. If you ask local health officials and community leaders, there is no single reason for it. Instead, a complex network of existing infrastructure that predates not just the vaccination process but the pandemic itself is a huge factor.

“The health care in a community is about an entire system; it’s not just one department. And part of that system is our press is good, our health department is good, our hospital is good, our care homes are just outstanding,” County Commissioner Barb Kickhaefer says.

The way Sue Rhodes, a registered nurse and the administrator of the Marshall County Health Department, sees it, the high vaccination rate can be traced back to decades of work in the county to build a health care system built on trust, community partnerships and neighborly connections.

“We went at it that these are our people, and we need to take care of them,” Rhodes says.

Trust built on familiarity

One interesting dynamic is that Marshall County residents already depended on the health department for vaccinations long before there was COVID-19 or even a vaccine for it. The department’s staff of nurses has regularly provided age-specific and annual immunizations. That’s unusual because people don’t usually go to a local health department for their flu shots, choosing primary care physicians or a pharmacy instead.

“There’s no one or no place in our county that gets vaccines,” Rhodes says, “so we vaccinate probably 90% of the county.”

When it came time to start giving COVID-19 vaccines to the general community in the early months of 2021, people were already used to making a trip to downtown Marysville for an immunization appointment. Marysville is the county seat and largest city, but Marshall County is also home to Blue Rapids, Frankfort, Waterville, Axtell and a few other small towns.

The goal of the health department throughout that process was the same as it had been with any other vaccination effort.

“We’re trying to get the most amount of vaccine in their arms,” Rhodes says.

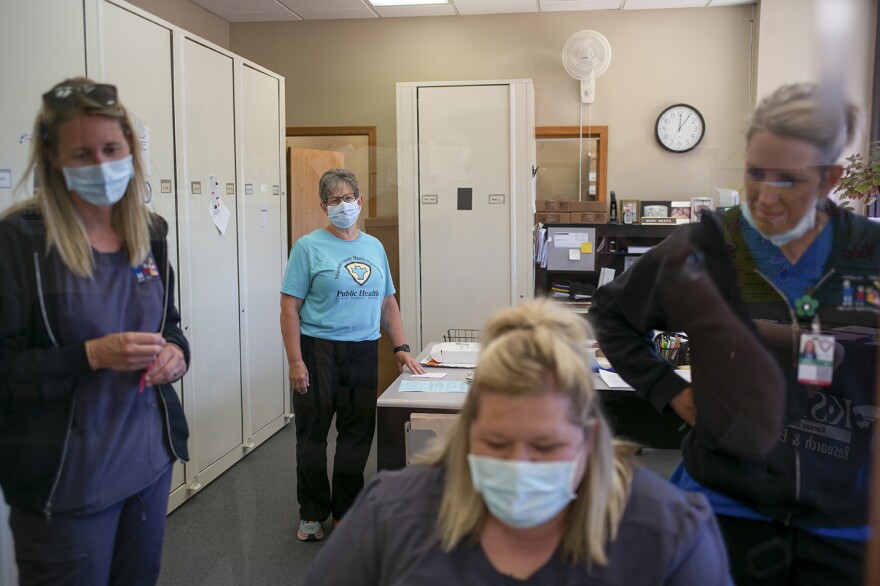

While it’s a hub for immunizations, the health department’s staff – Rhodes, four nurses and two office workers — happens to be geographically dispersed so that just about every county resident can easily get first-hand advice.

“Everybody in the county knows someone that’s employed here,” Rhodes says. “That helps build a rapport. It helps build trust.”

In this case, the rural nature of the community actually strengthens the public health system.

“People know each other; neighbors talk to each other,” Rhodes says.

When you know all of your neighbors, there’s a deeper connection to them, which can inspire more compassion for those impacted by a major crisis, says Kickhaefer, the county commissioner.

“We don’t want people to die,” she says. “We want our kids to go to school. I want my neighbors to feel as safe as possible, and if I can do that by getting a vaccine, that’s a small thing to do to make someone feel safe.”

An older population with long memories

Marshall County is also home to a concentrated population of people who are 65 and older, a group more likely to take vaccines, Rhodes says. According to the U.S. Census data, roughly 21% of the county is 65 or older.

Not only was that age group most at risk of developing serious infections and dying from COVID-19, but they have also experienced previous major health crises in their lifetimes, Bill Schwindamann, the county’s emergency management director, says.

Fritz Blaske, another county commissioner, remembers the panic caused by polio that swept the country during his childhood.

“I had an uncle that went in a wheelchair because of (polio),” Blaske says.

When he was in elementary school, the polio vaccine was approved and there was a rush to get it. That’s why, when this vaccine was authorized and it was available to him, he put his name on the list.

“There just wasn’t a decision — you just did it,” he said.

That’s a common sentiment, Rhodes says. In some cases, she says older residents felt it their duty to get the vaccine as soon as it was offered to them. Not only was it the ticket back to a sense of normalcy, but for some, they saw it as one more step toward protecting the community from COVID-19.

Getting a head start

In addition to work applied to build a foundation of trust in the local public health system pre-COVID-19, Schwindamann said local health officials were working on a plan to administer vaccines early on.

“We just didn’t start this process in January,” Schwindamann says. “We started (talking) way back in March (2020), about what’s happening, what can be done, the possibilities of vaccines coming, what can you do to prepare yourself, what are the side effects.”

Schwindamann says Community Memorial Healthcare, a 23-bed critical access hospital in Marysville, was already working to gauge the community’s willingness to receive the vaccine as early as fall 2020 by launching a phone hotline for people to register their interest and ask questions.

“We did answer a lot of phone calls initially, and then after a while, people just left their name and their phone numbers and stuff on those lists,” Deb Hedke, the hospital’s director of infection prevention, says.

By the time the vaccines arrived, the details were settled, Ashley Kracht, the hospital’s director of public relations and marketing, says.

“The both of us kind of together have partnered in figuring out how that was going to happen in making that happen,” Kracht says.

Aside from a mass vaccination effort early on in the rollout, the doses are distributed much like every other vaccine. The health department serves as the primary vaccinators, but they work off the list of names from the hospital. With each vaccine allocation, Rhodes says, she calls the hospital and tells them how many doses are available. The hospital then helps fill those appointments.

“That allowed them to have more time to get their stuff done and not have to make all those phone calls,” Hedke says.

Falling short of herd immunity

Marshall County’s success at vaccinating shows that low population density need not be a limiting factor, says Dennis Kriesel, executive director of the Kansas Association of Local Health Departments.

“The Marshall County Health Department has indicated it has been working one-on-one with residents to answer vaccine questions, and that sort of direct outreach is the prime way to address hesitancy concerns as it allows public health to respond to specific questions in individualized and meaningful ways,” Kriesel says. “Generalized outreach campaigns can struggle because their structure is often more broadcast-style with little ability to answer detailed concerns people may have.”

Marshall County, he says, may also benefit from its lower population size as smaller communities often consist of residents that know each other.

“The trust level is naturally higher between those who know each other versus strangers, and thus Marshall County may be seeing the benefits in their vaccination effort thanks to having high inherent trust levels between the residents and the vaccinators already,” Kriesel says.

However, the uptake hasn’t been universal. Despite its high rate of vaccination, Marshall County has yet to reach the herd immunity threshold, which is reached once 75% to 80% of a population has become fully immunized. The vaccine is being studied but has not been approved for use in children under age 12, meaning some members of the population can’t be immunized yet.

But whether the county has a path to reaching herd immunity level of vaccination is unclear.

“I don’t know that we’ll get there,” Rhodes says.

That divide is starting to become clear, Kickhaefer says. For several weeks the county saw very few new cases of COVID-19 and low levels of transmission, but the trajectory is starting to change. That resurgence could go a long way to persuade people on the fence to get the vaccine, Kickhaefer says.

“That might make people want to take the vaccine even more when they see that the only people who are getting the virus are people that refuse to take the vaccine,” she says. “I think people that are dead set against it are never going to change their mind. They’re always going to think that it’s something they don’t want to do.”

Hedke says now that the county has completed vaccinating everyone who was really eager to get the vaccine, she’s confident there are more people who can either be persuaded to get the vaccine or will decide to get it at a later date.

Some people are already starting to change their minds, Hedke says, especially people who were eligible in Phase 1 who decided to wait.

“They wanted to watch and see what the response was with everybody else – make sure they didn’t grow horns and all that,” Hedke said. “Once they decided that everybody did pretty well, then they were willing to go that direction.”

A different struggle everywhere

However tempting, Rhodes doesn’t think Marshall County and its general success in the vaccine rollout can be easily replicated elsewhere. For one thing, the work that led to the high degree of vaccination began years ago.

Even then, Rhodes thinks it’s difficult to compare the work of other health departments with her own.

“That’s hard to really justify because the makeup of every county is different and the makeup in health departments are different,” Rhodes says. “I think that every struggle every health department has is probably different.”

Roughly one-third of county health departments have lost their top officials over the course of the pandemic, according to The Kansas City Star. Some were threatened or harassed.

Rhodes says larger counties, like Wyandotte County, have big populations that make it more difficult to build the types of community relationships that Marshall County has relied on throughout the pandemic.

Smaller counties have fewer resources to put toward public health measures, even in an emergency, which might leave one or two people in charge of the whole pandemic response.

“I think that every public health person should have a pat on the back by everybody in their community because they’ve had a heavy cross to carry in the last year that is probably going to be continued to be carried for some time in the future,” Rhodes says.

Kaylie McLaughlin, of Shawnee, is a reporter and editor for a digital news startup called the Olathe Reporter in Johnson County. She is a proud alumni of Kansas State University and the former editor-in-chief of the campus’ independent newspaper The Collegian. She completed this assignment for The Journal between graduating and starting at the Olathe Reporter.

You can find her on Twitter @Kayliemc_laugh.