Today, in service to our spring book club on mystery and suspense novels, I thought we’d talk about what I call the art of suspense—that is, the various methods writers use to keep readers turning pages.

If you asked a lot of crime readers how authors create suspense, many of them would probably say, “I keep reading to find out who the murderer is.” And that’s fair, oftentimes we do keep reading to see who committed a crime.

But often that’s not the case at all. In fact, as I discussed in another one of my bookbytes, the genre of “suspense”—as it’s usually defined in the publishing world—doesn’t involve a whodunnit at all. Think John Grisham, Tess Gerritsen or James Patterson. In most of these authors’ books, we know who is committing the crimes. But we keep reading to see how it all plays out.

When I think of the “art of suspense,” I remember an essay I read in The New York Times a few years ago. The piece was by another writer of suspense thrillers, Lee Child, author of the Jack Reacher series. In his essay, Child laid out his deceptively simple method for creating suspense. Child says he’s asked frequently how to create suspense, and he compares it to the question, “How do you bake a cake?” Both of these questions, writes Child, are too indirect. They miss the point. Instead, we should ask, “How do you make your family hungry.” And the answer? “You make them wait four hours for dinner.”

The application of this lesson, in fictional terms, means that Child opens up a ton of questions in his narratives—then waits to reveal the answers. And, whenever he gives readers the answer to a question, he asks another one. These questions act like Reese’s Pieces in the movie ET—they keep the reader inching along, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, page by page.

These mysteries don’t have to be epic, like the identity of a murderer. They could be small, the recognition of a face in a crowd—the face of a woman who isn’t identified for another page. Or, a bump in the next room, a sound whose source isn’t revealed for several paragraphs. Or a trauma that happened to the protagonist as a child, that is merely hinted at for the first 100 pages. This lesson can and should be applied to the writing of fiction, whether you’re writing crime or romance or literary novels.

Child has given us a nifty trick here, and a useful one, but for me, this isn’t the main way that an author should create suspense. To me, suspense—like almost everything else in fiction writing—should be derived from character. What I mean is, fictional protagonists should have, at their core, a conflict so dynamic that it keeps readers turning pages to see whether that internal tension is going to snap.

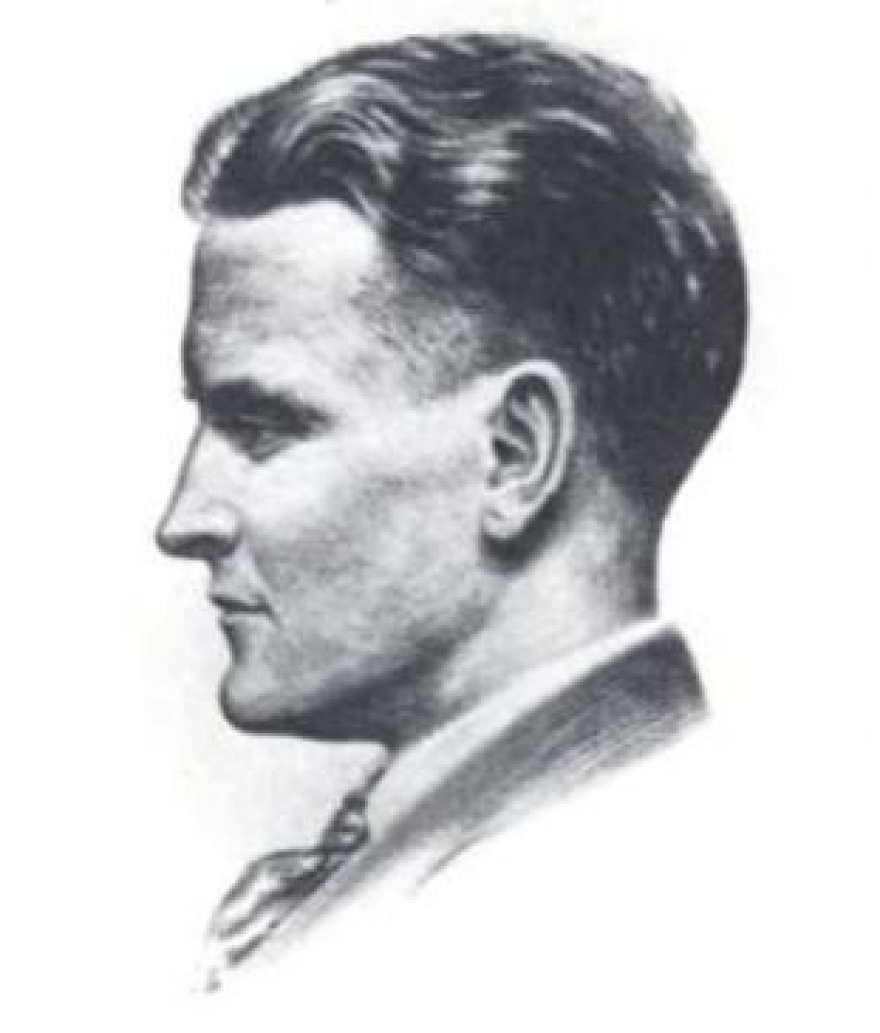

Take a novel like The Great Gatsby—not really considered a suspense novel, yet readers have been turning the pages for almost a century. Why? Because they want to see if Gatsby will attain his ultimate goal of winning Daisy Buchanan’s heart, yes. But more than that, it’s what Daisy means. Winning Daisy would represent, for Gatsby, the final sloughing off of his hardscrabble past, when he was the penniless James Gatz of North Dakota.

Fitzgerald’s novel hums like a taut wire, with the tension between Gatz and Gatsby, those opposite personas who come to represent past and future, truth and lies, poverty and wealth, and so much more. The conflict within that character is an eight-cylinder suspense engine, and it has propelled The Great Gatsby into the pantheon of America’s finest novels. Read Fitzgerald and witness a master at the art of suspense.