I’m Dennis Garcia and I’m a Boomer, born in 1951 in Garden City, Kansas. Ten years earlier on December 7, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Days later, the U.S. entered World War II and required males, age 18-65, to register for military service.

My father, Dionicio, and his five brothers registered as ordered. Like most families on the High Plains, the brothers believed military service was a duty owed to the country.

They viewed the challenges of service as another job to do, just like the challenges they overcame during the Great Depression and Dust Bowl. But Mexican men also saw an opportunity with their call to duty: military service, especially combat, could support their demands for treatment as first-class citizens in the United States.

My uncle Felipe, an older brother, became an Army Corpsman and was sent to Pearl Harbor four months after the attack, but he contracted strep throat. His illness was misdiagnosed, and he was treated for a common cold. As a result, he suffered the worst complication of strep throat, heart damage. Felipe was medically discharged in 1943 and returned to Garden City where he fought his illness until his death in 1957, at age 39. Uncle Miguel served in the army and saw combat in the South Pacific.

My mother, Irene, was born in Dodge City, about fifty miles from Garden City. Her brother, my uncle Salvador Rodriguez, also served during World War II. He was sent to the Ardennes Forest in eastern Belgium in November of 1944, a month prior to the Battle of the Bulge which sealed Germany’s defeat in Western Europe. My grandmother, Rafaela, kept a small altar with votive candles where she prayed for the safe return of Salvador and the other boys from the Mexican Village.

Dodge City’s segregated Village was located adjacent to the Santa Fe Railroad’s tracks on the city’s southeast side. Nearly a dozen of the Village boys served in Europe, including three brothers of the Esquibel family, Roberto, Rodolfo and Miguel. Both Roberto and Rodolfo were killed in 1944, Roberto in July, and Rodolfo in December. Only Miguel returned. The Esquibel family became one of the thousands of American families who made the ultimate sacrifice.

In May 1945, the war in Europe ended, but Rafaela still received no word from Salvador. Weeks later her ten-year-old son, Gonzalo, returned from an errand to a neighborhood grocer. Gonzalo told Rafaela that he had good news. The grocer said his son, also serving in Europe, sent word that he was on a ship with another guy from Dodge City, and they were coming home. The grocer also told Gonzalo the other guy was named Salvador Rodriguez. Rafaela burst into tears, and immediately knelt at her prayer altar, giving thanks to God. Salvador was coming home.

On their return to the states, Mexican veterans began to organize to end discriminatory practices at home. While violent race-motivated crimes against people of Mexican ancestry in Garden and Dodge City were few, the slights were frequently open. My mother, in line to buy war rationed bed sheets, was told to take her place at the end of the

line; my father, in army uniform sitting next to his light skinned brother, was refused service at a diner; movie theaters imposed balcony seating; and access to the public pool was denied.

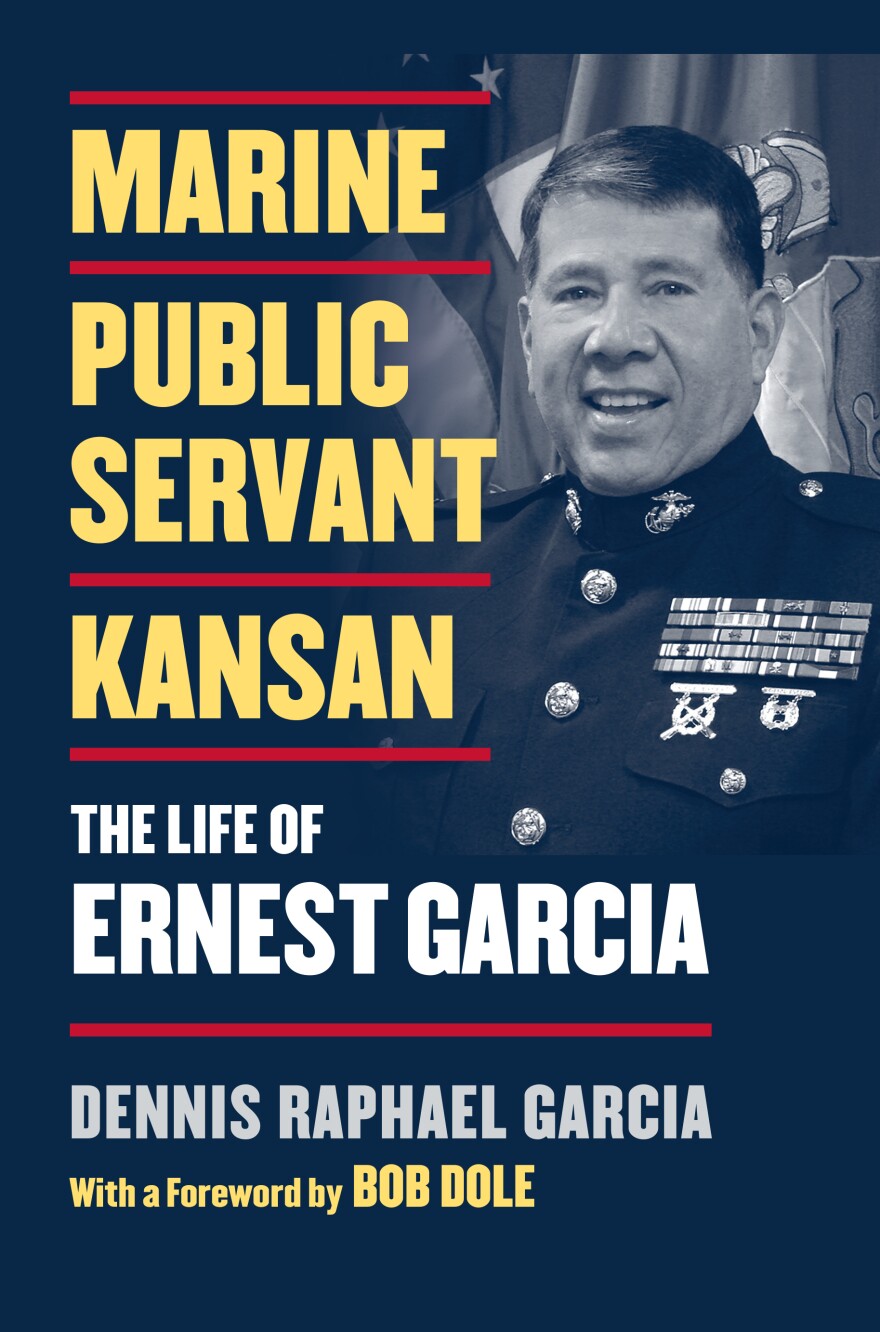

Mexican communities began to confront city and business leadership and demand that these racist practices end. A generation later my cousin Ernie took advantage of the opportunities the war veterans fought for. He served as a Marine officer in both the Gulf and Iraq Wars and later served as the first Hispanic Senate Sergeant at Arms

I’m Dennis Garcia, author of Marine, Public Servant, Kansan: The Life of Ernest Garcia, it’s available from your favorite online retailer and through the University Press of Kansas. My thanks to High Plains Public Radio.