For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favorite podcast app.

On July 26, 1990, protesters, grassroots organizers, lawmakers and everyday Americans showed up in droves to the South Lawn of the White House to watch President George H.W. Bush sign the Americans with Disabilities Act into law.

“This is an immensely important day. A day that belongs to all of you,” Bush told the crowd of 3,000. “And everywhere I look, I see people who have dedicated themselves to making sure that this day would come to pass."

The ADA guaranteed equal opportunity for people with disabilities in public accommodations, employment, transportation, state and local government services, and telecommunications.

Now, 35 years later, the ADA is ingrained in how America builds buildings and does business.

But most people don’t realize how close the law came to not passing. It took years of debates between politicians and advocates — not to mention protests, lobbying and back-door negotiations.

People from every state played a part, but Kansas took on a larger role than some — because Kansas is the home of Bob Dole.

The late Republican U.S. Senator was one of the co-sponsors of the ADA — and the sixth person President Bush thanked on that hot, July day.

“The message to America by passing this bill is that inequality and prejudice will no longer be tolerated,” said Dole in a statement after the bill passed. “We need this legislation not only because it is just and fair for people with disabilities, but because all of us can benefit from the talents and abilities of all Americans.”

‘He never forgot he came from Russell’

Dole believed in the power of teamwork to make people’s lives better.

It’s one of the many values the one-time presidential nominee credited to his hometown: Russell, Kansas. A tiny city of less than 5,000 people, about two and a half hours west of Topeka.

Dole’s love for Russell was such common knowledge, in fact, that it was the plot of a 60-second Super Bowl commercial in 1997.

Before Dole represented the state of Kansas for 35 years in Congress, he was a charming soda jerk at his local drug store. And a basketball star recruited to the University of Kansas by the famous coach Phog Allen.

But he didn’t stay at KU very long. He left to fight World War II — and it nearly killed him.

Three weeks before the end of the war in Europe, Dole’s platoon got caught in a fire fight in Italy. Shrapnel blew apart his shoulder and arm, and broke several vertebrae in his neck and spine. For a time, he was paralyzed from the neck down.

For years, Dole was in and out of hospitals, bed-ridden for long periods of time. He used to play the song, “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” over and over again on repeat.

“I drove my parents crazy, playing it on the record player we had,” he told NPR in 2005. “But I think the deeper meaning is that I knew that I wasn't walking alone. I had my parents. I had the doctors. I had the nurses.”

He also had the people of Russell, who established the Bob Dole Fund. They raised money for his surgeries by putting out a cigar box at the local drug store, the same one where he used to serve milkshakes and ice cream floats.

Dole never regained use of his right arm. But with everyone’s support, he got healthier — and decided to pursue a career in politics.

“I used to say, if I can’t use my hands, I’ll use my head,” Dole told Fresh Air.

Dole in Washington

Dole was elected to the Kansas House of Representatives in 1950, while he was still a student at Washburn Law School. And in 1960, the city of Russell helped send him to Washington — to four terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, and then to represent all of Kansas in the U.S. Senate.

Dole became known as a hardline fiscal conservative. But he also supported the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Sen. Bob Dole made his first speech on the Senate floor in 1969, on the 24th anniversary of the day he was wounded in World War II. In it, he called for public and private-sector commitments to improve the lives of Americans with disabilities.

“We have only begun to help guarantee that each handicapped person and his family enjoy complete dignity, independence and security,” he said.

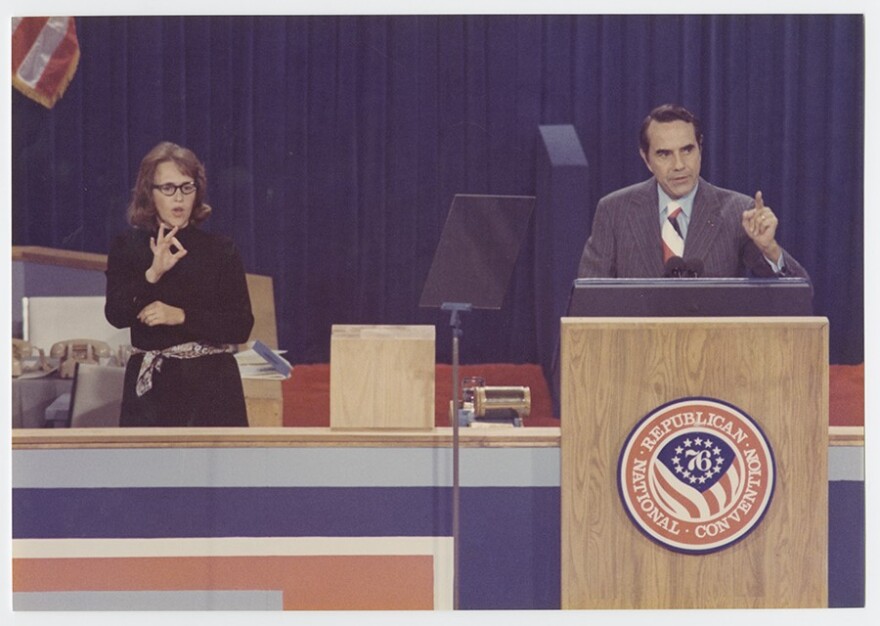

Dole became a household name in 1976, when President Gerald Ford chose Dole as his running mate. Dole’s nomination was cemented at the Republican National Convention, which was held in Kansas City that year, and his speech was interpreted into sign language.

During his time in Congress, Dole authored a law that prohibited airlines from discriminating against people with disabilities, and called for closed-captioning in U.S. Senate proceedings.

He also supported Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities for all programs receiving federal funds.

“Section 504 is a bill of rights for America’s handicap,” Dole said in a 1976 speech. “The Department of Health, Education and Welfare is in the final stages of a wide ranging public review of the regulations implementing Section 504. And President Ford and I believe — and strongly believe — that should be completed as quickly as possible.”

It took nearly four years for Section 504 regulations to be signed, in April 1977, and only after protesters put pressure on federal health officials by staging a series of highly publicized and disruptive sit-ins in federal buildings across the country.

Even then, the huge limitation of Section 504 was that it only applied to institutions that received federal funding. And advocates, including Dole, wanted public accommodations in the private sector, too.

That’s one of the things the Americans with Disabilities Act was written to solve.

'An emancipation proclamation for disabled Americans'

One of the many people who spearheaded the Americans With Disabilities Act was Justin Dart, a polio survivor and wheelchair user. Widely called the “father” of the ADA, he helped write the initial draft that was introduced in Congress in April 1988.

As federal lawmakers began debating the bill, Dart came to Kansas City on a cross country road trip. And during an hourlong forum, he asked people with disabilities what challenges they faced.

According to the Kansas City Times, “witnesses aired their complaints as if cleansing wounds.”

A woman with a spinal cord injury spoke up about the humiliating time a local restaurant refused to host her birthday party. A woman with epilepsy shared that a bus driver once ordered her to get off the bus for fear she might have a seizure. A man in crutches complained that because of his disability, he was told to enter a restaurant using the back door.

These are the kinds of everyday injustices that the ADA promised to protect people from.

In Congress, what Bob Dole brought to the table was personal experience, an empathetic ear, and a unique ability to negotiate across the aisle.

Sen. Tom Harkin, a Democrat from Iowa who helped introduce the ADA, called Dole their “linchpin to the Republicans.”

Dole would explain to Democrats the problems Republicans had with the bill, so they could fix them.

Business groups were among the biggest roadblocks — requiring accessible ramps and other building accommodations would cost some serious money.

To Republicans and other critics, he would frame the ADA as good for the economy overall, and a way for more people to participate in the workplace.

“Bob Dole was an excellent compromiser, but he wanted something left. He didn't want to give it all away and compromise it down to a meaningless piece of legislation,” says John D. Kemp, co-founder of the American Association of People With Disabilities.

Dole was the Senate Minority Leader at the time, but he was always available to chat with a disability advocate, says Mo West, a legislative aide who advised Dole on disability issues.

“He basically gave me carte blanche to bring anybody in from a Kansas disability group,” says West.

‘It wasn’t just a protest. It was a turning point’

Nearly two years after the ADA was first introduced, it was still being debated in the U.S. House of Representatives — and activists were sick of waiting around.

“It is an emancipation,” Dole told “Good Morning America” on March 12, 1990, when asked about the ADA. “We’re the largest and probably the poorest group that’s not protected by civil rights protection.”

Organizers planned several demonstrations, including a march that ended up marking a turning point in the disability rights movement.

The same day that Dole appeared on national television, hundreds of disability rights advocates — organized by the group ADAPT — marched from the White House to Capitol Hill chanting “ADA now!” and “Access is a civil right.” But they didn’t stop there.

At the Capitol, 60 protesters abandoned their wheelchairs, crutches, and other mobility aids, and slowly, painstakingly climbed up the 83 steps however they could. The youngest among them was just 8 years old.

“The images of that are iconic, right?” says Rebekah Taussig, author of “Sitting Pretty, The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body.”

“Like, you have the capital towering. And then these people pulling their bodies up the steps to demonstrate the spectacle of inaccessibility. This is what this looks like. If this is uncomfortable to you, it should be.”

Dole wasn’t at the protests, but his legislative aide, Mo West, attended with his full support. The next day, she watched as 200 advocates occupied the Capitol’s Rotunda. More than 100 were arrested.

“They weren't gonna move until they got a commitment that this bill would continue to move in the House,” West recalls. “Many legislators that were involved in the ADA came over and said, ‘We're gonna move this. We hear you, we see you. This is really important.’”

West says those very visible, and nationally televised, demonstrations raised awareness and interrupted politicians’ workdays. They were a major impetus in getting the U.S. House to finally pass the Americans with Disabilities Act — which it did just four months later.

“Don't underestimate the power of collective advocacy,” West says. “The ADA didn't pass because the system was ready. It passed because people demanded it.”

Less than five years after the Capitol Crawl, Dole successfully lobbied the Architect of the Capitol to install a ramp, making the Old Senate Chamber accessible to people who use wheelchairs and other mobility aids.

An unfinished legacy

Thanks to the Americans with Disabilities Act, the country has seen a generation of people grow up in a completely different world — one with closed captions on television, crosswalk signs that tell you when it’s safe to go, disability parking permits, and accessible bathroom stalls.

Even if you don’t think you benefit from the ADA, you do.

Take something like a curb cut, that ramped section of a sidewalk, as one example. It’s great for wheelchair users, but it’s also a benefit for someone pushing a stroller, using a walker, rolling a suitcase or riding a bike.

Bob Dole often called the ADA his proudest legislative accomplishment. He went on to champion disability rights until he died in 2021 at the age of 98.

Part of his legacy included supporting initiatives like the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which took its inspiration from the ADA. It’s since been ratified by nearly every country in the world — except for the United States.

In 2012, Dole came to the Senate floor to watch the vote.

“Don’t let Sen. Bob Dole down,” urged Sen. John Kerry. “He is here because he wants to know that other countries will come to treat the disabled as we do.”

Then, from his wheelchair, Dole watched as a majority of Republicans voted down the treaty, over concerns it would infringe on American sovereignty.

Perhaps, to the retired Republican from Kansas, it made him remember his very first speech in the U.S. Senate, 44 years before: “Our handicapped citizens are one of our nation’s greatest unmet responsibilities and untapped resources. We have done well, but we must do better.”

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced, and mixed by Mackenzie Matin. Editing by Suzanne Hogan and Gabe Rosenberg.