HAYS, KANSAS — Even for a perennially dry region like western Kansas, this year sticks out.

Barely any rain. Temperatures that bake the soil into a cracked, parched mess. And forecasts that don't offer much hope of relief.

This summer in Dodge City ranks as its 5th hottest on record. And this year is the southwest Kansas city’s 12th driest in history going back to the 1870s.

And Dodge City is merely one hot, dry spot in a state that’s only occasionally found itself this warm and parched.

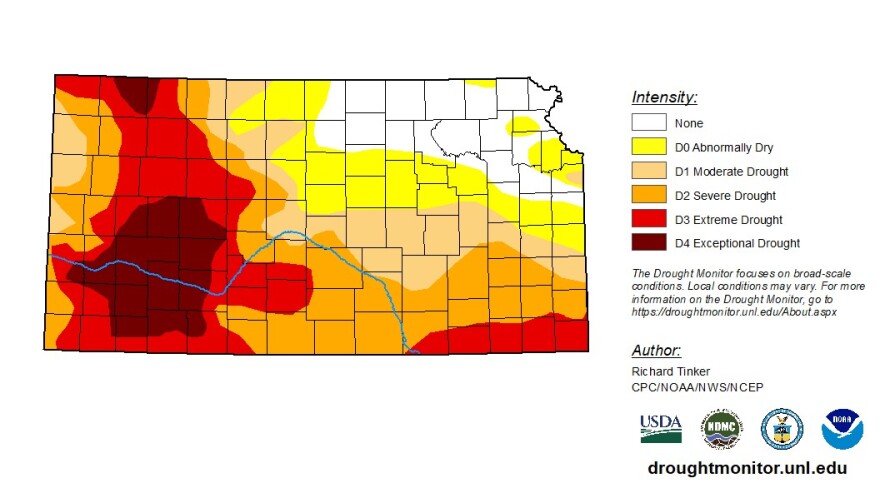

Drought currently covers nearly three-fourths of Kansas. And roughly one-third of the state is in extreme or exceptional drought — the highest levels on the U.S. Drought Monitor scale.

But is 2022 one of the worst drought years in the state’s history? It depends on how you look at it.

“It is bad, but it’s not near as bad as it has been,” National Weather Service meteorologist Jeff Hutton in Dodge City said. “It's been far, far worse than this.”

That doesn’t mean 2022’s drought hasn’t had grave consequences. The timing and location of some of this year’s harshest conditions devastated crops, as western Kansas wheat farmers saw earlier this summer.

But dry, hot weather is nothing new in this semi-arid part of the world. And experts like Hutton and Kansas State University meteorologist Chip Redmond said frequent breaks in the heat and timely bits of moisture have kept 2022 from surpassing the records set by the most extreme years in Kansas history.

- Here's how this year's drought has battered the Midwest — and what it might mean for next year

- This city in Kansas really conserves its water, but that still might not be enough to survive

- One year after wildfires, Kansas ranchers vow to ‘get by ... somehow’

- Western Kansas wheat crops are failing just when the world needs them most

- How the drought killing Kansas corn crops could make you pay more for gas and beef

- Up to 1 million birds count on Kansas wetlands during migration. Drought has left them high and dry

- How Kansas could lose billions in land values as its underground water runs dry

- As fertilizer pollutes tap water in small towns, rural Kansans pay the price

- Kansas wildfire responders brace as a dangerously dry, windy season drags on

- How an increasingly brutal Kansas climate threatens cattle’s health and ranchers' livelihoods

- A hotter, drier climate and dwindling water has more Kansas farmers taking a chance on cotton

That illustrates the complexity of trying to compare one bad year with another.

“We can look at basic statistics, such as average monthly precipitation and temperature and their departure from normal,” said Redmond, who manages K-State’s Kansas Mesonet climate monitoring system. “(But) that doesn’t tell the whole story.”

Based on historical data, he said, the years that top the charts for drought and heat in Kansas history came during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s — particularly 1934 and 1936 — and then in 1956, 1974, 1976, 1980, 1983, 2000 and 2011-2012.

So, how does 2022 measure up against those benchmark years? Here are seven ways to compare them.

1. Dry spells

Rainfall totals this year are several inches below normal across Kansas. Hays has received around 9.5 inches of precipitation so far in 2022. That’s roughly half of the 18 inches it can usually expect to bank by this time of year.

Hutchinson has seen fewer than 14 inches of precipitation when it’s supposed to have more than 22 inches. Only 6.5 inches have fallen on Scott City — way less than its usual 15 inches.

Here’s another way to look at it: How many inches of rain would a town need today in order to get back in line with its historical year-to-date average?

For places like Hays, Hutchinson and Scott City, it would take more than eight inches of rain to climb out of their current deficits. Some pockets of northwest, central and southeast Kansas would need more than 10 inches of rain just to get back to average.

But even with how dry it’s been this year, 2022 doesn’t come close to being the driest in Kansas history.

“This year has quite a bit of work needed,” Redmond said, “if it wants to rank high.”

Out of 358 Kansas weather stations measuring precipitation, none have recorded their driest-ever 40-day period in 2022. That’s compared to 46 stations that set records for their driest 40-day period in 2000, 39 that set records in 1983 and 10 that still have records standing from the Dust Bowl in 1936.

2. Summer rain

In this traditionally dry region, annual precipitation averages are already measured in inches instead of feet. So when parts of western Kansas miss out on their precious few chances for summer rain — as has been the case this year — it particularly stings.

“The majority of our precipitation anywhere in the High Plains comes during the warm season from thunderstorms,” Hutton said, “So typically, you're not going to get a lot of precip in the late fall (or) wintertime that's going to alleviate the drought.”

A lack of moisture can directly fuel hotter temperatures, too. The drier soil gets, Hutton said, the faster it heats up.

But this summer still doesn’t hold a candle to the driest summers of years past.

Only one location in Kansas is on track to set a new record for its driest summer this year. Girard in southeast Kansas has received just over 2 inches of rain from the start of June to late August. That’s compared with 26 locations that experienced their driest June-August period in 1980 and 41 stations that set records in 1936.

It’s also worth noting that there are considerably more weather stations active today than there were in 1936, which makes it all the more remarkable that so many precipitation and heat records still stand from the Dust Bowl era. The Girard weather station, for example, didn’t begin monitoring until 1957, so one of those earlier years might actually have been drier than 2022.

3. 100-degree days

One way to assess this year’s heat is to compare the number of days that reached 100 degrees.

In Wichita, 23 days have hit that mark so far this year. In northwest Kansas, the town of Atwood has seen 31 of those days. Ashland in southwest Kansas leads the state with 39 days.

Those figures run well above average. Ashland’s total is more than double the number of 100-degree days the town has normally racked up at this point in the year. Wichita’s total puts 2022 in the top 10% of its recorded history.

But it’s still not close to breaking records.

“I’ve already heard people say, ‘Oh, it’s the hottest year ever,’” Hutton said. “No, it’s not. We only have to go back 11 years to 2011.”

Dodge City set an all-time record with 50 days of 100-degree weather that year. So far in 2022, it has seen 31 days that hot.

While that doesn’t come close to touching 2011’s record, it still means that 2022 already has the sixth most 100-degree days ever recorded in Dodge City.

4. Back-to-back days of heat

Unlike the most extreme years in Kansas history, this year’s 100-degree days have been much less likely to be strung together consecutively.

Ashland had 23 consecutive 100-degree days back in 1954 and 22 in a row in 1934. This year, it’s had two separate streaks of six days. That’s just the 81st longest streak in Ashland history.

Wichita experienced 20 days in a row in 1936 and an 18-day streak in 1980. Its longest run in 2022 was five days in a row. That’s Wichita’s 47th longest streak ever.

Hays saw streaks of 18 days and 15 days in 1934 and a streak of 17 days in 1980. This year, its longest streak is only three days, which is actually tied for the shortest streak in Hays history.

The number of consecutive 100-degree days matters because the heat’s impact — on people, crops and the environment — is multiplied as more extremely hot days fall back-to-back.

“When considering flash — or rapid onset — drought,” Redmond said, “stringing together consecutive hot days is important.”

5. Hot high temps

So far this year, seven of 159 Kansas weather stations have set new records for their hottest average high temperatures over a 20-day period.

That’s bad news for those seven locations. But statewide, that total pales in comparison to the 42 stations that have records still standing from 1980 or the 31 stations still holding on to records from 1936.

The actual temperatures this year haven’t been quite as hot as past record years either.

The state’s two all-time hottest 20-day periods both happened during the Dust Bowl — an average of 110.2 degrees in Winfield (1936) and Lincoln (1934). The hottest 20-day average of the seven new records set this year is several degrees below that — 102.7 degrees in Garden City.

I saw a bunch of sad corn fields like this one while I was in Finney County.

— David Condos (@davidcondos) July 26, 2022

The months-long drought — paired with recent 100-degree temperatures — has fried a lot of the #westernkansas corn crop. pic.twitter.com/ivcXV1xTDG

6. Afternoon highs and overnight lows

Another way to look at heat is to compare a combined average of the high and low temperatures. This shows not only which years had the hottest afternoon highs, but also which years had the warmest overnight lows.

Climate change has slowly increased average low temperatures across Kansas since 1970 — nights have gotten 2.7 degrees warmer in Wichita. Dodge City recorded its warmest nighttime low temperature ever this June. And those rising nighttime temps can have destructive effects on crops and livestock.

But 2022 still falls far short of being the state’s hottest year by this measure as well.

In all, only seven of 159 Kansas weather stations set a new record for the hottest combined average temperature across a 20-day period in 2022 — compared with 40 records that still stand from 1980, 39 records from 2011 and 25 records from 1934.

And the record temperatures in 2022 aren’t as hot as their counterparts from past years.

The warmest 20-day period for combined high and low temperatures happened in 1980 when Wichita, Eureka and Anthony all recorded averages of 93.4 degrees. The comparable highest temperature from a record set this year — 85.3 degrees in Liberal — is several degrees cooler than that.

7. What happens next

One thing we don’t know yet about this year’s drought? When it will end.

Some of the most destructive droughts in Kansas history spanned multiple years. Depending on whom you ask, the Dust Bowl lasted somewhere between six and 10 years during the 1930s. A decade ago, Kansas experienced two historically dry, hot years back-to-back in 2011 and 2012.

Just like the compounding power of consecutive 100-degree days, having dry years back-to-back amplifies the damage those years inflict. Some parts of western Kansas saw the current dry spell begin to creep in during the second half of last year as rain totals fell below average, which set them up to fall faster and harder into drought this year.

And if the current drought continues into next year, Hutton said, that’s when it would be time to reassess 2022’s place in history.

“If I felt that we were going to be in a super dry pattern for two or three years,” Hutton said, “then we'll start looking at that 1956 drought, look at the 2011 drought, 2012 drought … and just compare the aerial extent and the severity of it.”

But he said that’s unlikely to happen. Long-term forecasts point toward Kansas getting more rain next year than this year, even though next year’s precipitation totals will likely remain below-average.

What’s happening in 2022, Hutton said, is just part of the natural weather cycle in this near-desert region.

Dodge City actually enjoyed above-average precipitation for seven straight years from 2013-2020. Prior to that, the southwest Kansas city had never experienced more than three years in a row of above-average rainfall.

So after decades of periodically extreme weather, he said, Kansans who farm this land should expect a year like this to come around sooner or later.

“They know that they’re going to have to endure these bad years,” Hutton said, “before we get back to the good gravy train.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of High Plains Public Radio, Kansas Public Radio, KCUR and KMUW focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.