HAYS, Kansas — This state knows something about dry spells, high winds and the out-of-control fires that can follow.

So it might be easy for recent alerts that have warned Kansans about dangerous wildfire conditions to fade into the background.

But Chip Redmond, a volunteer fire captain in rural Pottawatomie County, said the ferocity of the wildfires he’s seeing in northeast Kansas this spring make this season feel different.

“It’s burning more aggressively. It’s burning hotter,” he said. “It’s harder to put out.”

- Here's how this year's drought has battered the Midwest — and what it might mean for next year

- This city in Kansas really conserves its water, but that still might not be enough to survive

- One year after wildfires, Kansas ranchers vow to ‘get by ... somehow’

- Here are 7 ways this dry, hot year stacks up against the worst droughts in Kansas history

- Western Kansas wheat crops are failing just when the world needs them most

- How the drought killing Kansas corn crops could make you pay more for gas and beef

- Up to 1 million birds count on Kansas wetlands during migration. Drought has left them high and dry

- How Kansas could lose billions in land values as its underground water runs dry

- As fertilizer pollutes tap water in small towns, rural Kansans pay the price

- How an increasingly brutal Kansas climate threatens cattle’s health and ranchers' livelihoods

- A hotter, drier climate and dwindling water has more Kansas farmers taking a chance on cotton

Kansas has seen short snapshots of similar dry, volatile fire conditions in recent years. But this winter and spring, those snapshots have been strung together into a months-long horror show.

It’s getting harder to prevent the statewide tinderbox from igniting. And with drought conditions expected to drag on into the summer, there’s little relief on the horizon for the state’s wildfire responders.

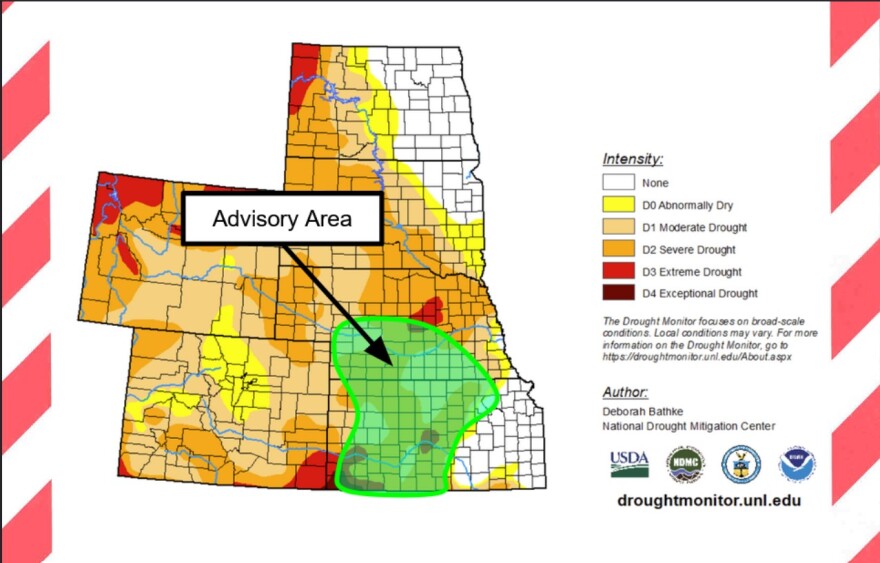

Redmond, who’s also a meteorologist with the statewide monitoring system Kansas Mesonet, issued a fuels and fire behavior advisory this week warning of a “volatile landscape for extreme fire” in Kansas through late April. It’s the first time this type of advisory has been issued in the state since 2018.

Fire teams he’s talked with recently have told him the strategies they’ve used to suppress wildfires in past years aren’t working as well now. And even if they can get a blaze under control, the smoldering embers have been more likely to reignite.

That means firefighters have to pour more time — and water — into each fire to make sure the flames don’t flare up again a day or two later. His crew responded to 13 fires in the past week, including some calls that turned into day-long battles to beat back long lines of burning grass.

That comes on top of a long-standing problem: Volunteer fire departments across the country are strained as rural populations drop. Since 1984, the number of volunteer firefighters nationwide has fallen 17%, while calls for their help have tripled.

Redmond said the number of volunteers in his rural department isn’t what it was even 10 years ago. And for the remaining firefighters who have already faced months of dangerous conditions dating back to the widespread fires last December, the ongoing inferno leaves them frustrated and exhausted.

“We are worn out. Equipment has been breaking because it’s just been used excessively,” Redmond said. “It’s running us ragged.”

Ugh. Enough. pic.twitter.com/4yxQTTJelx

— Chip Redmond (@wx_chip) April 12, 2022

Blame it on the rain

So what makes this spring an especially treacherous time for wildfires?

It may be hard to believe, but one of the big factors fueling the current danger is too much rain — last year.

Before the drought set in, the state got some timely precipitation that spurred extra grassland growth. For example, last year brought Wichita’s fifth wettest March on record.

All that rain was great news for cool season grasses, which grew taller and more abundantly than usual. But by the time winter arrived, those grasses were dead.

And now, they’ve turned into tall piles of dry kindling that blanket much of the state.

Mark Neely, fire management officer with the Kansas Forest Service, said drought-prone places like western and central Kansas have to straddle a fine line between too much or too little rain.

“If it’s a dry year, we want rain to mitigate the hazard,” Neely said. “But then when we do get the rain, all we do is say, ‘Well, crap. Now it’s gonna be more grass for next year when it’s dry again.’”

That’s where Kansas sits now — left with an extraordinarily high fuel load in the form of dry grass that could potentially burn in a fire.

Then there’s the drought that has gripped much of Kansas for months since the state's warmest December on record.

Persistently dry air masses covering Kansas evaporate what little moisture ends up on the ground before it can do much to counteract the drought. In these conditions, Redmond said, it only takes about an hour for wet grass to dry out enough to burn extremely efficiently.

It’s been windier than normal too. Redmond said statewide wind speeds in March were nearly two miles per hour faster than average.

And the relief that usually comes with spring hasn’t arrived yet.

Normally by this point of the year, new green grass begins to overtake the dead grass left from the previous year. That’s a big help for firefighters because the new grass isn’t as combustible as dead grass — it holds more moisture — and therefore keeps fires from becoming so large and destructive.

But the drought has stunted its growth.

“The green grass that’s coming up now is so small in proportion,” Redmond said, “It’s not slowing fire down because there’s so much dead grass above it.”

Neely, the forest service official, said when an area’s burning index — a measurement of the destructive power of a fire based on the available fuel — is consistently above the 90th percentile, that’s a trigger point for the state to increase firefighting resources. And he’s been seeing those types of extreme levels across the state for weeks.

It’s especially dire in north-central and northeast Kansas, where wildfire danger indicators have been at or near record levels for more than a month.

“We are at some critical stages in our fuels,” Neely said. “Wind and temperature is just going to exasperate that unless we get that good green-up and some more moisture.”

But the Kansas fire season — which would normally begin wrapping up around this time of year — may be long from over.

Redmond said weather projections indicate that above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation could continue to push fire conditions to dangerous levels for the rest of this spring and into the summer.

“Everything is (pointing) the wrong way right now,” Redmond said.

The #wildfire season has been off to a busy start for the high plains and southwest. @NIFC_Fire recently updated their outlooks pointing to the active season across those regions potentially continuing through #July. #Drought #FireWx pic.twitter.com/ur9nDMf6Vu

— Dr. Stephen Bieda III (@DrWildcatWx) April 9, 2022

‘One of those years’

In western Kansas, Scott County emergency management director Tim Stoecklein said he has felt a heightened sense of alert this week, as the region inches closer to its most significant drought in a decade.

“There’s been a lot of comparisons to 2012,” Stoecklein said. “This feels like one of those years.”

Each day, he goes through a mental checklist to make sure he’s prepared for whatever comes. Talking with his fire department to check that the water tankers are ready. Asking neighboring counties if they need any help. Checking with the local National Weather Service office about the forecast.

Here’s how the wildfire response process generally works. When someone sees a fire, they call 911 and the local fire department responds. Usually, the local squads can handle things.

But not always.

This week, a task force from Johnson County helped fight fires in Ottawa County. State aircraft dropped water on fires in northeast Kansas. Vehicles and a team leader on loan from a neighboring state assisted local firefighters with a blaze in southwest Kansas’ Ford County.

And wildfire preparedness isn’t just about responding after an emergency happens. This week in Scott City, a forest service training event proactively removed downed trees and other debris that could kindle fire at a nearby state park.

Stoecklein said homeowners can mount their own defenses by storing firewood at least 30 feet from a house, trimming back trees, clearing out gutters and leaf piles.

“That’s all fuel,” he said.

It’s also vital to have an evacuation plan if your home lands in the path of a fire. So have a bag packed with everything you need for a few days and know where to turn for fire updates if an emergency arises, such as alerts from the regional National Weather Service office or the local emergency management department.

“I want folks to not be surprised,” Stoecklein said. “It’s better to be prepared than scared.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.